written by history graduate assistant Miles A. Abernethy

Introduction

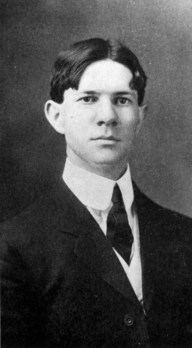

Earlier this month, I completed researching and putting together an exhibit on the professional life and legacy of Dr. James I. Robertson Jr. Known to friends and fans as “Dr. Bud,” Robertson taught Civil War history at Virginia Tech for over forty years, from 1967 to 2011. Even before the term came into vogue, he taught the Civil War like a public historian, seeking to appeal to broad audiences. He achieved this through vivid storytelling, connecting people to the lived experiences of Civil War figures and making events long past seem moving and compelling. His classes at Virginia Tech appealed to all majors and class levels, regularly teaching over one hundred students every semester for most of his time at Tech. Robertson can be said to be part of the university’s growth, especially in the nascent History Department, lending his skills to grow the department as well as the liberal arts broadly. The exhibit covers Robertson’s contribution to the Civil War Centennial Commission, as well as his life and legacy connected to Virginia Tech. I want to share my experience with the collections I used, as well as how I thought about this exhibit, Robertson, and Civil War history in general.

Ironically, I used very little of Dr. Robertson’s own collection (Ms1994-021 James I. Robertson Jr. Papers), and the making of this exhibit was a way for me to identify how the collection can be used, and if it can be expanded. I actually processed a new accession to the collection in 2022 which included his filing system for Virginia units in Confederate service and for Civil War history of Virginia’s counties and cities. In addition, this accession included records on Robertson’s involvement with battlefield preservation, and correspondence with fellow Civil War historians. However, if interested parties want to gain a better understanding of Robertson’s teaching and non-publishing life, they would be disappointed, as the collection is about two-thirds of book drafts for Robertson’s major publications in the 1990s and early 2000s. Luckily, SCUA holds a record group for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies (RG 21/8 Virginia Center for Civil War Studies), the Civil War academic center that Robertson founded in 1999. This collection contains papers regarding Robertson’s founding and running of VCCWS through his retirement in 2011, as well as documents from outreach events from the 1970s through 2000s. It also has papers concerning Robertson’s tenure as chair of the History Department from 1969 to 1977. It is from this collection that I gathered most of the extant papers and information about Robertson’s professional life at Virginia Tech.

Two other collections proved useful as well. The J. Ambler Johnston Papers (Ms 1974-012) contains correspondence between Johnston and Robertson. Johnston, a 1904 Virginia Tech graduate and career architect, took special interest in Civil War history and communicated regularly with Robertson on the Civil War and on Virginia Tech matters before his death in 1974. Robertson’s biographical Vertical File also proved extremely useful, containing information about Robertson’s perception in the wider Virginia Tech, state, and national community. Helpfully, it also has an article on Robertson’s job as a football referee for the Atlantic Coast Conference, a part of his life that I really wanted information on. While these other collections helped build out the exhibit, they highlight the fact that Robertson’s own collection is severely lacking in information about his non-publishing academic and personal life. What is and isn’t in a collection is the choice of the archivist, the late Robertson, and his living relatives, but as a significant figure in Civil War historiography, public history, and Virginia Tech, we ought to have more information in a centralized collection about him.

Civil War Centennial Commission

Unfortunately, one of the most impactful episodes of Robertson’s life is essentially absent from the extant archival materials, beyond a few articles and mentions: his work on the Civil War Centennial Commission from 1961-1965. The Civil War Centennial Commission (CWCC) was active from 1957 to 1965, and sought to organize public commemorations of the war’s one-hundredth year. Robert Cook’s Troubled Commemoration (2007) is the current authoritative work on the subject, and focuses on the developments and hurdles faced by the Commission. Conceived by Civil War historians and amateur “buffs,” factions soon emerged in the national and state organizations on the best way to organize events and by what means. Professional historians clamored for a serious and academic remembrance, while business figures argued for more popularly accessible events. Sectional divisions became even more salient as Congressional leaders were appointed to the commission; Northern and Southerners clashed as debates over whose version of Civil War history would prevail. The state commissions, ostensibly under the purview of the national leadership, took their own approaches that varied between the sections.

Tensions came to a head in April 1961 when the CWCC planned to hold its fourth annual conference in Charleston, South Carolina to commemorate the beginning of fighting at Fort Sumter. Officials feared for the safety and inclusion of Madeline Williams, a Black woman on the New Jersey state commission. Segregationist commissioners worked to block Williams’ attendance, in concert with other efforts to block what they saw as revisionism to their “Lost Cause” understanding of the war. With the Commission teetering on failure, President John F. Kennedy stepped in, pressuring the CWCC to meet at desegregated federal military bases. Unwilling to acquiesce to Kennedy’s compromise, many of the staunch segregationists resigned, allowing professional historians to take more active leadership. Leading the revived CWCC were Professors Alan Nevins and James I. Robertson.

Cook characterizes Robertson generally as an effective and straightforward executive that had a genuine interest in telling a serious but appealing story of the Civil War to the American public. Even more important was the pairing of Nevins and Robertson: a Northerner and Southerner respectively, that seemingly balanced any sectional preference that detractors of the CWCC were eager to point out. The Commission’s fortunes soon improved, and Robertsons former professor Bell I. Wiley of Emory noted that he “works hard, maintains a cheerful outlook and wins friends for himself and the Commission by his open cordiality.”1 The new professionalism of the CWCC earned praise from Kennedy, resulting in an awards ceremony with the President in which Robertson was present. The image of both figures is on display in the exhibit.

Robertson was a product of his time however, and his appointment as the executive director under Alan Nevins was a strategic move to satisfy the worries of the segregationists who feared that the CWCC would become a tool of the Civil Rights Movement. While Cook describes Robertson as genuinely committed to positive civil rights change in the South (albeit at a gradual pace), he recognized that the success of the CWCC required working with conservative Southern commissioners and telegraphing some of their feelings into the national commission. Cook reflects one of these unfortunate moments, as Robertson generally chafed at a request by Nevins and Wiley to write African American soldiers as playing a larger role in winning the war for the Union in a student handbook.2 Despite a conservative historical outlook, Robertson’s work helped cement the centennial as an important historiographic moment. Although the public largely lost interest in the commemorative activities after 1961, the stabilization of the CWCC helped maintain academic and public interest in the Civil War through the twentieth century.

Time at Virginia Tech

I contend that Robertson’s time as a professor at Virginia Tech is his most important contribution to the public vitality of Civil War studies as well as the study of the liberal arts at Virginia Tech. Arriving in 1967, Robertson’s public popularity helped grow the fledgling History Department in its early years. His successful tenure as chair between 1968 and 1977 is indicated by the steady growth of bachelors and masters degrees awarded during that same time, as well as an expansion of history curriculum.3 This is all accomplished while Virginia Tech was, and remains, an engineering and science-focused institution. Robertson’s style of storytelling-teaching attracted history and non-history majors alike, and his wider popularity meant that his Civil War classes were usually attended by hundreds of students. One amusing document that is featured in the exhibit is an October 2000 memo from Associate Vice President Thim Corvin to Robertson concerning the total number of students that had attended Robertson’s classes. Corvin’s office presumably underestimated the number, prompting Robertson to respond with his own personal data that he spent a whole evening compiling, along with some remarks about the effectiveness of Corvin’s people. According to his data, Robertson had taught over twenty thousand students by the late 1990s. If we take that at face value, then by his retirement in 2011, Robertson likely taught over thirty thousand students during his time at Virginia Tech.4

Robertson was a public historian before the term became vogue in history circles, seeking to appeal to broad audiences. In addition to his classes, he organized and led outreach classes and events beginning in the late 1970s. Although classes and lectures had long been part of offerings by Civil War Round Table organizations, Robertson’s partnering of academic prestige with public outreach meant that people who had passing interest in the war or wanted to take a specific course could do so through extension classes. Early organized lectures included the “Campaigning with Lee” series, as well as a featured lecture that Robertson delivered in Squires Student Center in 1979.5 By the early 1990s, steady attendance at these public events prompted Robertson to begin the Civil War Weekend conference in 1992 that continues to this day. Events like these bring the public into spaces with professional historians, enhancing everyday understanding of the Civil War, its meaning, and the historical agents that took part.

Legacies

Dr. Robertson passed away in November 2019, right as I was beginning my time as an undergraduate at Virginia Tech. At that point, I hadn’t decided on a career in Civil War public history and wasn’t really aware of the Civil War history significance of Virginia Tech. I was, however, aware of Dr. Robertson and the emotional connection that he fostered between himself and his students and the war they all studied. I recall meeting people at Civil War Weekends or on online forums that describe the loyalty that he inspired in students, even on a generational level. My father, Robert Abernethy, is a 1990 Virginia Tech graduate and took Dr. Robertson’s Civil War class. We have a signed copy of Robertson’s A.P. Hill: Story of a Confederate Warrior that my dad had signed while he was a student. His academic interest in the war was invigorated by Robertson, and he passed that passion onto me.

Robertson’s professional guidance influenced many historians today. Jonathan Noyalas, a Virginia Tech Masters alumnus who studied under Robertson, is head of the McCormick Civil War Institute at Shenandoah University. Patrick Schroeder, a Virginia Tech student who attended Robertson’s earliest classes, now serves as Historian at Appomattox Court House NHP. Chris Mackowski, author and editor-in-chief of Emerging Civil War noted in a tribute that Robertson instilled in him the confidence and reassurance that newer historians need to stake out on their own.6

Robertson’s work is felt directly at Special Collections and University Archives. His work to donate thousands of Civil War era books and manuscripts has elevated SCUA to one of the largest repositories of Civil War information in the United States. I always like to tell people why I study the Civil War. Plainly put, it is America’s most defining event. Even one hundred and sixty years later, Americans are living out the changes in government, politics, war, and society that the conflict produced. Like the war that he devoted his life to studying, Dr. James I. Robertson has left us a complex legacy, but one that has elevated our understanding and appreciation for the quintessential American experience.

- Robert Cook, Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial, 1961–1965 (Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2007), 218.

- Cook, 222.

- George G. Shackleford, “Department of History at VPI & SU,” RG 15/13 Department of History.

- “Memo to Thim Corvin,” RG 21/8 Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Box 1, Folder “Student Solicitation.”

- “Gone With The Civil War: History that Historians Overlooked” Virginia Tech Union’s “The Not Your Average Lecture Series,” MS 1994-021 James I. Robertson Jr. Papers, Oversize Folder 1.

- “Tributes to James I. “Bud” Robertson Jr.,” Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, Accessed November 19, 2024. https://civilwar.vt.edu/tributes-to-james-i-bud-robertson-jr/.